Salmon and Sea Trout Facts & Recognition

Wild Atlantic salmon and their cousins, sea trout, have a fascinating and varied lifecycle, with many similarities but also key differences. Both species are often encountered by anglers and other water users, and having the knowledge to distinguish between the two can be helpful.

How do you tell the difference between Salmon and Sea Trout?

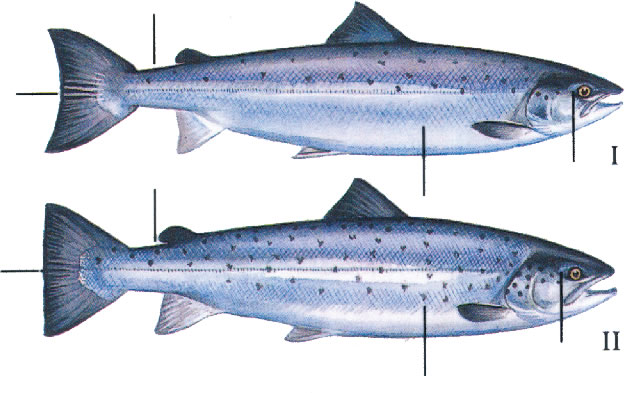

Adult salmon (I) can be distinguished from large adult sea trout (II) by a more streamlined shape, concave tail, slimmer tail wrist, upper jaw reaching no further than rear of the eye, few if any black spots below lateral line, 10-15 (usually 11-13) scales counted obliquely forward from adipose fin to lateral line – trout have 13-16.

| Salmon | Sea Trout | |

| General appearance | Slender and streamlined | More round and thickset |

| Head | Pointed | More Round |

| Position of the Eye | Maxilla (bony plate usually alongside mouth) does not extend beyond rear of the eye | Maxilla extends beyond the eye |

| Colour | Relatively few spots | Often heavily spotted |

| Scale count (number from adipose fin to lateral line) | 10-13 | 13-16 |

| Fork of tail | Usually forked | Usually square or convex |

| Wrist of tail | Slender | Broader |

| Handling | Easy to grip and keep hold of the ‘wrist’ of the tail |

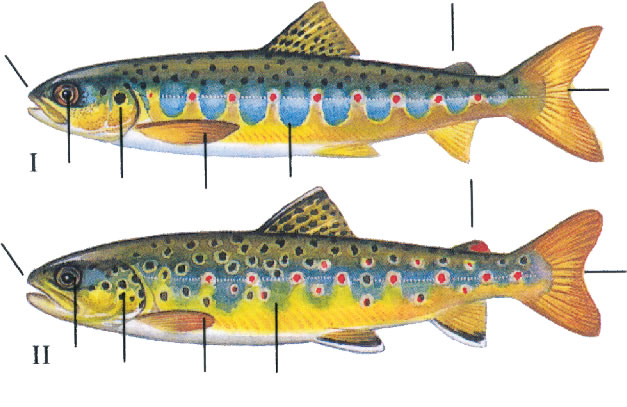

The image below shows a juvenile salmon parr (I) and a small brown/sea trout (II). Juvenile salmon parr can normally be distinguished from young brown/sea trout by the more streamlined shape, deeply forked tail, longer pectoral fin, lack of orange on adipose fin, smaller mouth, sharper snout, only 1-4 spots on gill cover (often one large spot), well defined parr marks.

What should anglers look out for to help identify their catch?

Biologists who work with salmon and sea trout often mark the fish that pass through their hands in any of the ways depicted below. The capture of a marked salmon should be reported at once to the appropriate fishery authority. Frequently the address is on the tag or mark. Usually, the information required is date, place, and method of capture; length, weight, and sex of fish and a sample of scales taken from between the dorsal and anal fins at above the lateral line.

Notes:

- Tagging should be carried out only by trained and authorised personnel.

- Fins that have been clipped do, with the exception of the adipose, regenerate.

- The adipose fin should not be removed, as clipping is internationally recognised as an indication that the fish has been micro-tagged.

- If adipose clipped fish are killed, the head (where the micro-tag is located) should if possible be sent to the nearest fisheries laboratory.

What does anadromous mean?

The Atlantic salmon and sea trout are referred to as being anadromous because of its habit of migrating from the sea into freshwaters to spawn. This is the exact opposite of the common eel which leaves freshwaters to spawn in the Sargasso Sea, and is therefore called catadromous.

What is osmoregulation?

Osmoregulation is the control of the levels of water and mineral salts in the blood. All fish that migrate from freshwater to saltwater during their life cycle must go through this process.

The salmon is an excellent osmoregulator. However, like virtually all osmoregulators, the salmon is never in true equilibrium with its surroundings. In the ocean, the salmon is bathed in a fluid that is roughly three times as concentrated as its body fluids, meaning that it will tend to lose water to its surroundings all of the time. And, because the composition of its body fluids is so different from the ocean water, the salmon will be faced with all manner of gradients that are driving exchanges that will continuously tend to drive its body fluids’ concentration and composition beyond homeostatic limits. In particular, the very high concentration of NaCl (sodium chloride) in the ocean water relative to its concentration in the salmon’s body fluids will result in a constant diffusion of NaCl into the salmon’s body. Unless dealt with effectively, this NaCl influx could kill the salmon in a short time. In sum, a salmon in the ocean is faced with the simultaneous problems of dehydration (much like a terrestrial animal) and salt loading.

However, in freshwater, the problem is basically reversed. Here, the salmon is bathed in a medium that is nearly devoid of ions, especially NaCl, and much more dilute than its body fluids. Therefore, the problems a salmon must deal with in freshwater environments are salt loss and water loading.

How Does The Salmon Solve Its Osmoregulatory Problems?

Fortunately, the salmon has some remarkable adaptations, both behavioral and physiological, that allow it to thrive in both fresh and saltwater habitats. To offset the dehydrating effects of saltwater, the salmon drinks copiously (several litres per day). But in freshwater (where water loading is the problem) the salmon doesn’t drink at all. The only water it consumes is that which necessarily goes down its gullet when it feeds. Of course, when an ocean-dwelling salmon drinks, it takes in a lot of NaCl, which exacerbates the salt-loading problem. Kidney function also differs between the two habitats. In freshwater, the salmon’s kidneys produce large volumes of dilute urine (to cope with all of the water that’s diffusing into the salmon’s body fluids), while in the ocean environment, the kidneys’ urine production rates drop dramatically and the urine is as concentrated as the kidneys can make it. The result of this is that the salmon is using relatively little water to get rid of all of the excess ions it can.

Time course of the salmon’s acclimation responses

The behavioral (drinking or not drinking) and physiological changes a salmon must make when moving from freshwater to saltwater — and vice versa — are essential, but cannot be accomplished immediately. Thus, when a young salmon on its seaward journey first reaches the saline water at the mouth of its home stream, it remains there for a period of several days to weeks, gradually moving into saltier water as it acclimates. During this time, it begins drinking the water it’s swimming in, its kidneys start producing a concentrated, low-volume urine, and the NaCl pumps in its gills literally reverse the direction that they move NaCl (so that they’re now pumping NaCl out of the blood and into the surrounding water.

Likewise, when an adult salmon is ready to spawn and reaches the mouth of its home stream, it once again remains in the brackish ( i.e. less concentrated than full-strength seawater) water zone of the stream’s mouth until it is able to reverse the changes it made as a juvenile invading the ocean for the first time.

What do parr feed on when they are in freshwater?

The larvae of aquatic insects and other aquatic invertebrates together with terrestrial insects which fall into the water.

Do all Atlantic salmon migrate to sea?

No. Although most Atlantic salmon spend part of their lives at sea there are some who are non-migratory. In several lakes in eastern North America, there is a form known as a land-locked salmon, Salmo salar sebago (Girard), though their access to the sea is not barred. The fish is popularly called Ouananiche (Lake St. John) or Sebago salmon (Nova Scotia, Quebec, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, and the New England States). In Lake Vänern in Sweden there is a non-migratory form of Atlantic salmon called “blanklax”. Land-locked Atlantic salmon also occur in Lake Ladoga in Russia and in Norway in Lake Byglandsfjord. There are also land-locked Atlantic salmon in South Island, New Zealand.

What is a grilse?

A grilse is an Atlantic salmon which has spent only one winter at sea before returning to the river. Salmon grilse is often indistinguishable from multi sea winter (MSW) salmon except by scale reading. They are smaller on average (2-3lb in May, 5-7lb in July) but when they enter rivers in September often attain 8-10lb and in October 12-15lb.

How big can a salmon grow?

Atlantic salmon can grow to a very large size and the biggest, which have reached up to around 70lbs (32kg), are usually caught in Norway and Russia. However, some very large fish have been recorded in Scottish rivers. It is generally accepted that the largest one caught on rod and line in the UK was taken by Miss Georgina Ballantyne in the River Tay in 1922: it weighed 64lbs (29kg). There is an 1891 report of a huge salmon of 70lbs, also caught in the River Tay, but on this occasion in a net.

What is the largest salmon ever recorded?

The largest recorded Atlantic salmon, a male caught in Norway’s Tana River, weighed 35.89 kg. and was over 150 cm. in length.

How have salmon stocks changed over the years?

All around the North Atlantic, stocks have been in general decline over a number of years. Some population components, such as early-running or ‘spring’ fish, have suffered particularly badly. Actual population levels are difficult to estimate, except on rivers with reliable counting facilities such as the Atlantic Salmon Trust’s Core Rivers, but catch figures can be used to give an indication, particularly of trends.