SAVE THE SPRING – River Dee

Preserving the Wild – A strategic approach to support wild spawning and restore the Dee’s spring-run salmon

Goal 5: Create catchment partnerships to share successful solutions, supporting others to implement them in their own river catchments.

Save the Spring is a restoration programme located in the River Dee catchment in Aberdeenshire – delivered in partnership between the River Dee Trust, Dee District Salmon Fishery Board and Atlantic Salmon Trust, and supported by the University of Stirling and UHI Inverness.

It comprises a planned 20-year programme of work to restore and futureproof the upper River Dee catchment – heartland of its spring salmon. Aligned with our other work programmes and Core Rivers, the focus is on delivering cold, clean water in biodiverse landscapes which are resilient and adaptive to the impacts of climate change.

Background

As is the case with Atlantic salmon rivers across the North Atlantic, climate change is severely impacting wild Atlantic salmon populations in the River Dee, particularly the river’s iconic spring-run salmon which have declined by 80% in recent decades. In the upper parts of the catchment, some of the river’s spring-run Atlantic salmon subpopulations are now at risk of extinction. As an alarming example, the Girnock Burn, which is dominated by spring-run multi-sea winter Atlantic salmon, has recorded the decline in female fish returning to spawn, from as many as 200 females in the 1960s, to just 1 female in 2024.

Rising water temperatures and altered flow patterns are creating significant challenges for long-term salmon survival and reproduction success. Winters are becoming wetter, leading to more frequent and severe flooding events which can wash away salmon eggs and young fish, risking the loss of entire generations. The loss of riverbed stability due to frequent winter floods has also impacted salmon spawning areas, invertebrate populations, and other species such as freshwater pearl mussel. A study carried out on the River Dee near Banchory found that only 10% of the catchment’s substrate was in a stable condition in 2023, down from 50% in 2010.

Conversely, the spring and summer months are becoming drier with snowpack on the Cairngorms decreasing, resulting in periods of low water flow and higher temperatures. Recent studies have shown that water temperatures in the River Dee have increased by an average of 1.5°C over the past three decades. This change can have profound impacts on the river ecosystem, particularly for cold-water species like Atlantic salmon. Higher water temperatures lead to reduced oxygen levels. increased stress on fish, poorer juvenile growth rates, and altered timing of important lifecycle events such as spawning and migration.

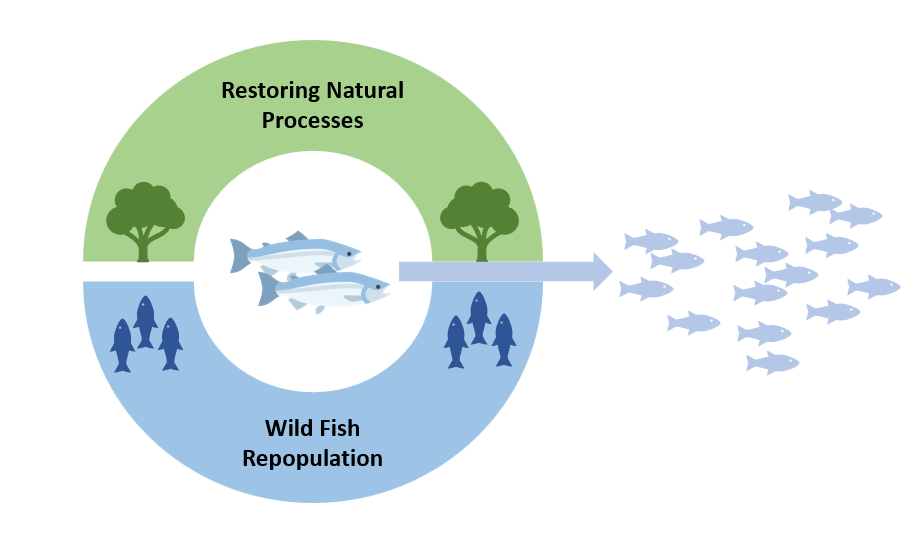

Upper tributaries, key to spring salmon spawning and juvenile production, are now frequently exposed to high water temperatures and low flows. 60% of monitoring sites in the upper Dee in 2023 for example exceeded temperatures that cause thermal stress to salmon. Save the Spring is now taking action to restore natural processes in the landscape to protect against these climate impacts and allow wild Atlantic salmon and other wildlife to recover. At the same time, as some salmon populations are now critically low, a careful helping hand is being given to the wild salmon population to help it on this recovery, maintaining the catchment’s unique wild salmon genetic diversity to enable them to adapt to the challenges of the present and future. The programme therefore employs a two-pronged strategy, combining landscape-scale habitat restoration with wild fish repopulation to enable increased wild spawning.

Element 1: Habitat Restoration – Building resilence, adaptability and biodiversity

The habitat restoration element of the strategy aims to, among a number of goals, slow the flow of water off the landscape. This will ultimately reduce the power of flood events and over time improve the river’s stability. Key to slowing the flow is a complex riverside zone involving restored native woodland, as well as peatland and wetland restoration in the wider catchment. The programme is prioritising tributaries upstream of Aboyne, comprising approximately 1000km2 in area and 900km of stream length, 300km of which is already highlighted as at risk of thermal stress.

Programme partners identified five priority tributaries for the first phase in 2024. Of these, the River Muick has been the focus for the wild fish repopulation pilot. The Muick was identified as a key initial focus area, based on its critically low salmon population status, its good geographic catchment access and existing working partnerships in place, an absence of impassable barriers, and improving habitat quality and water quality due to restoration work and recovery from historic acid rain impact. Other tributaries the partnership will work on in the next five years are the Clunie, Feardar, Gairn and Girnock.

Element 2: Wild Fish Repopulation Pilot – Supporting wild spawning

The UK’s only smolt-to-adult supplementation programme rearing wild salmon in land-based, closed containment saltwater facilities.

Genetic diversity has enabled wild Atlantic salmon to be adaptable to change, a feature of the species which is especially important to preserve in the face of the rapid climate and environmental change of today’s world. Preserving this diversity is key to the second half of Save the Spring – wild fish repopulation.

How our pilot differs from traditional stocking

Unlike a stocking programme, which is typically defined as the artificial augmentation of natural salmon production by the addition of artificially-extracted eggs or young fish bred in captivity, this programme’s approach to wild fish repopulation does not propose to use fish as broodstock, extract salmon eggs from fish, hatch fish in captivity or stock artificially hatched fish into the wild. Instead, the approach is one of ‘conservation translocation’ – the movement of individuals of a species from one place to another for conservation benefit. In this case, wild fish will be captured and moved into captivity, reared to maturity, and then released back into the wild, at the same location from which they were captured, in order to spawn in the wild – an approach focused on wild spawning adults and wild hatched offspring.

Evidence demonstrates that hatchery-raised stocked salmon survive poorer over the course of their lifecycle when compared to wild hatched fish, and exhibit natural selection towards the domestic environment over several generations – i.e they become adapted to the hatchery and not to the wild. In the long-term, the programme’s ambition is to have secured the Dee’s unique populations of spring salmon in order to step back and leave behind a self-sustaining wild population, not run a continual artificial stocking programme which puts the long-term genetic integrity of these populations at risk and reduces their natural ability to adapt to a changing climate.

The main method of wild fish repopulation being trialled is smolt to adult supplementation and release (known as ‘S2A’), through which the programme partners are working with both the Scottish Government’s Marine Directorate and NatureScot to develop a detailed plan to ensure best practice. The S2A work is being carried out in partnership with the University of Stirling’s Institute of Aquaculture, with genetic information being analysed by UHI Inverness.

In April 2024, 87 wild smolts from the River Muick priority area were successfully transferred into the programme. As of April 2025 there have been minimal losses in this group and the fish are currently being cared for in the University of Stirling Institute of Aquaculture on-shore marine facilities on the West Coast of Scotland. A ‘soft transfer’ process was undertaken when the smolts arrived, gradually increasing water salinity over the course of a few days, before achieving a 100% saltwater environment for optimal feeding and growth.

All Muick smolts captured have been genetically sampled and this will allow us to understand the genetic structure of this subpopulation in order to maximise restoration efforts. This will provide a baseline to monitor their future spawning success, and the survival of their offspring. It has been highly encouraging to see how these now ‘post-smolts’ are feeding and growing in captivity. If all goes well, we hope to be releasing mature adult salmon back into the Muick to spawn in late 2025, creating wild hatched juveniles which can inhabit areas where native woodland restoration, peatland and wetland restoration has also occurred.

Demonstrating Success – It’s in the genes

Demonstrating success in the Save the Spring programme will come down to effective monitoring and reporting. Key to this will be genetic monitoring which can map the parental lineages of juveniles caught in the wild to match them up with fish from the rearing programme. For example, if we electro-fish an area where S2A has previously taken place, we will be able to tell from genetics which wild fry and parr were hatched from the wild fish we previously interacted with. Sampling migrating smolts caught in traps will then allow us to calculate the overall juvenile production resulting from our repopulation efforts.

Over time the partnership hopes to demonstrate the successful link between its habitat restoration and wild fish repopulation efforts, resulting in a recovering spring salmon population with its genetic integrity preserved and able to adapt to a changing world.

Where to find programme updates

Subscribe to our email newsletter to receive regular updates on Save the Spring, as well as our YouTube channel for occasional video updates. You can also scroll back through our news feed to find previous programme updates.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. A loss of riverbed stability and salmon redds (nests) being washed out from damaging floods seems to be a key issue in the upper catchment. How can habitat restoration improve the situation?

The habitat restoration element of the strategy aims to, among a number of goals, slow the flow of water off the landscape. This will ultimately reduce the power of flood events and over time allow the river’s stability to settle and heal. Key to slowing the flow is riverside woodland restoration, and peatland and wetland restoration, using methods such as leaky dams to hold water back and allow it to enter the river channel more gradually. Many of these actions can bring immediate benefits, as well as longer-term ones.

2. How much habitat is the project looking to restore?

The programme is initially covering the river and tributaries above Aboyne, which is approximately 900km of stream length and around 1000km2 in area. The restoration strategy is being developed so that the partnership can prioritise sites for work, using information we have about their current status (e.g. salmon populations) and pressures (e.g water temperature predictions). For example, 300km of streams are already highlighted as at risk of thermal stress.

3. How wide and large do riverside buffer strips need to be in order for them to have a positive impact on the aquatic environment?

The width of a riverside buffer strip and the management of its natural or semi-natural vegetation needs to be context-specific and take special account of the hydraulics of the river in the entire catchment. In general though, the bigger the buffer, the bigger the benefits to both the water quality and biodiversity.

4. The project concept mentions improving the estuary/marine transition zone. What does this mean and what can be achieved in this area?

Wild Atlantic salmon are vulnerable to impacts when transitioning between the freshwater and marine environment. In the Save the Spring initiative, the component of work focused on this area aims to define exactly what these impacts are (e.g flows, temperatures, chemicals, predators, disturbance) in Stage 1, and then develop solutions to alleviate any issues identified.

5. Do spring salmon not also spawn in the lower parts of the river system?

Yes they do, but we know that the upper parts of the catchment are the main spawning grounds for spring-running salmon so this is where our energy is best focused. What happens in the upper catchment also affects the lower catchment, so habitat restoration in these areas should bring benefits further downstream.

6. Is this a stocking programme?

No. Stocking is typically defined as the the artificial augmentation of natural salmon production by the addition of artificially-extracted eggs or young fish bred in captivity. This project’s approach to wild fish repopulation does not propose to use fish as broodstock, extract salmon eggs from fish, hatch fish in captivity or stock artificially hatched fish into the wild. Instead the proposed approach is one of conservation translocation – the movement of a wild species from one place to another for conservation benefit. In this case, wild fish will be moved into captivity, reared to maturity, and then released back into the wild, at the same location from which they were captured, to breed naturally.

7. Why are wild salmon genetics so important to preserve?

Genetic diversity has enabled wild Atlantic salmon to be adaptable to change, a feature of the species which is especially important to preserve in the face of the rapid climate and environmental change of today’s world. The Dee’s wild Atlantic salmon populations have adapted to the distinctive characteristics of the catchment over thousands of years and preserving this genetic diversity will give them the best chance of adapting to future environmental change and recovering to sustainable levels.

8. Why is the project choosing its wild fish repopulation approach over a traditional hatchery which grows salmon from eggs and releases them into the river as fry, parr or smolts?

The project believes in preserving and restoring the Dee’s wild genetic strains of Atlantic salmon and that is why the approach is focused on wild spawning adults and wild hatched offspring. Evidence demonstrates that hatchery-raised stocked salmon survive poorer over the course of their lifecycle when compared to wild hatched fish, and exhibit natural selection towards the domestic environment – i.e they become adapted to the hatchery and not to the wild. In the long-term, our ambition is to step back and leave behind a self-sustaining wild population, not run a perpetual artificial stocking programme.

9. What about using adult salmon as broodstock and then planting out fertilised eggs into the river? Would this not have the same ‘wild hatched’ effect but give you more control?

The project takes the approach that the wild Atlantic salmon in the Dee, which have adapted to their environment over thousands of years, should be allowed to go through their natural spawning behaviour – choosing an appropriate mating partner, building their redd (nest), choosing where to deposit their eggs, and choosing when to deposit their eggs. This approach allows wild Atlantic salmon to complete their natural lifecycle. Evidence supports the importance of preserving natural mate-selection behaviour in wild salmon to benefit offspring health, including wild Atlantic salmon.

10. Why is the project proposing to use facilities at the University of Stirling Institute of Aquaculture rather than a facility on Deeside?

Working with the University of Stirling will enable us to make use of the very best fish rearing facilities with a large, biosecure capacity to support the project as it grows, as well as to harness the vast experience and expertise of their staff. This experience will be invaluable when it comes to feeding, biosecurity, fish health and welfare, and maintaining the best possible environmental conditions for wild fish growth.

11. Will the smolts be reared in freshwater or saltwater?

Both. The University of Stirling’s facilities have the ability to transition fish between both freshwater and saltwater systems. This will allow us to best replicate natural conditions. Evidence indicates that saltwater growth produces more and better quality eggs than purely freshwater-reared salmon.

12. How many fish could the facilities handle and how many smolts does the programme hope to capture every year?

The facilities can initially accommodate the rearing of several hundred smolts, beginning with around 100 in the first instance. With careful forward planning, and agreed funding in place, there is capacity for this number to be increased in future years, with dedicated sections of the facilities being assigned exclusively to assisting with wild salmon restoration programmes.

13. How will the project monitor increasing fish numbers to demonstrate success?

Demonstrating success comes down to effective monitoring and reporting. Key to this will be genetic monitoring which can map the parental lineages of juveniles caught in the wild to match them up with fish from the programme. For example, if we electro-fish an area where wild fish repopulation has previously taken place, we will be able to tell from genetics which wild fry and parr were hatched from the wild fish we previously interacted with. Sampling migrating smolts caught in traps will allow us to calculate the overall juvenile production resulting from the repopulation methods.

14. Will in-river seal predation impact the project?

In-river seal predation has the potential to either prevent or slow the recovery of the river’s wild Atlantic salmon population. The Dee District Salmon Fishery Board is in conversation with Scottish Government and its agencies to seek support for management measures to reduce this pressure.

15. How is the project funded?

The first 5 year period of the project has a budget of £2m with £500,000 in private funding already raised. We are now actively fundraising for the remaining sums required to take the project forward.

16. Is any of the funding from salmon farming companies?

No.

17. Can members of the public get involved and volunteer?

When the programme is fully up and running we intend to create a volunteer registration portal so members of the public can join us and get involved in both the habitat restoration and wild fish repopulation elements of the project.

Next Steps & How You Can Help

Following our stakeholder engagement sessions and incorporating points which were raised during that process, our team is now busy developing the first 5-year stage of the project and preparing for the second round of smolt collection in Spring 2025. The project partners will report on the progress of these activities when able.

Fundraising – We need your support

You can support the Save the Spring initiative as an individual or an organisation. Every pound raised helps move the project towards its fundraising goal. Please contact our Corporate Ambassador, Mark Cockburn, to get in touch – mark.cockburn@atlanticsalmontrust.org

Volunteering – Boots on the ground

If you would like to register your interest as a project volunteer, either for the habitat restoration or fish capture elements of the programme, please contact the River Dee team at info@riverdee.org

Spread the word – Your voice matters

In order to maximise the potential of the Save the Spring initiative, we need you to help spread the word! Follow and share our #SaveTheSpring social media posts to help the project reach an even wider audience.